I’ve now gotten round to reading John Mackey’s op-ed in the WSJ on health care reform, the one that had me boycotting Whole Foods and all that. Here are some thoughts.

There are two big philosophical issues that underlie his piece and I’ll comment mostly on these. The first serious point is this. Mackey writes:

Health care is a service that we all need, but just like food and shelter it is best provided through voluntary and mutually beneficial market exchanges.

This suggests a dichotomy between things provided by “voluntary and mutually beneficial market exchanges” and things doled out in rations by the government like cups of rice from the government storehouse. But almost everything we need and consume comes to us under conditions that are intermediate between these extremes. As things stand in the US, food and shelter are not traded solely through voluntary market exchanges. Government subsidies affect what farmers grow; foreign policy affects what is imported and exported, as do currency and trade politics; the government’s control and maintenance of roads and airspace affects what gets sent where; government-backed scientific research affects agricultural technology and husbandry; the military’s development of the internet, of course, has affected everything; zoning laws, often made on political grounds, affect the availability and nature of housing; and so on. One way or another, then, government, policy and politics are pretty well intertwined with the market in food and housing.

Nor is the current ubiquitous provision of health care via insurance, whether government-backed or for profit, a pure voluntary market exchange. With respect to the provision of insurance itself, as Mackey notes, there are all sorts of regulations in place. Furthermore, something like 80% of the insurance market is “heavily concentrated,” that is, close to being monopolistic. Those who get their insurance through their employers usually have a single plan, or a choice of plans from a single provider, pre-chosen for them. Those who buy insurance in the individual market have few and unsatisfactory choices.

With respect to the relation between patients and health care providers (doctors, hospitals, etc.), things are complicated. In theory, this is supposed to be a voluntary market exchange and its terms should be quite independent of whether the users happen to have agreements with third parties for reimbursement through insurance. (And of course, when insurers fail to pay, the health care providers certainly don’t forget who actually is responsible for payment – the patient.) But in practice, things are quite different. Providers often bill insurers directly. This is, of course, often a great service to patients since medical billing is a field in which, literally, you can now get a higher degree. But the service also creates a situation in which it often seems as if the patient in not financially interested. Thus, doctors frequently order unnecessary tests without asking the patient first if they want to pay for it. Their reasoning is, undoubtedly, “why do you care? your insurance will pay anyway”. But whether or not the patient has insurance should not, in a pure market exchange between provider and patient, be any of their business. Nor is the patient well-placed to complain about unnecessary tests since the patient may never even see the bill, or it may be mixed in in some very complicated way, with a whole lot of other billing. So, if nothing else, the behavior of providers is greatly affected by their knowledge of the theoretically-irrelevant factor that the patient has a side agreement with a third party. It’s as if a teenager were to go to a car dealer and had to disclose ahead of time that their absent parent would foot the bill, whatever it is. This surely undermines the teen’s role as a party to a voluntary market exchange. What we often find now in health care is an almost institutionalized version of this situation.

So, to sum up this point: Rather than imposing an artificial dichotomy onto a fluid and messy situation that does not really fit, we should be asking where, from the point of view of social policy and overall well-being, we want to be on the continuum between lining up at the government storehouse and bargaining in a state of nature. All the proposals on the table lie in this intermediate area.

The second major point I take exception to in Mackey’s piece is this. He writes:

we need to address the root causes of poor health. This begins with the realization that every American adult is responsible for his or her own health.

If this just means that some of the things it is in our power to do or refrain from doing can affect our health, it is true but irrelevant. If it means, as it surely must for the logic of his piece to make any sense, that it is in our power to prevent ourselves from getting sick and hence, if anyone does get sick, it is his or her fault, it is so obviously false as to be laughable.

We cannot divide our ailments into the willfully self-caused, like those that result from smoking, and those that drop on us from above, like a girder falling from a crane. Many people, for example, in poor areas, may suffer from the results of bad nutrition but live without any access to affordable and healthy food, a fact that is at least partly the result of urban planning decisions, zoning laws, policing and education resources, and so on. Governments can regulate, or not, the toxins poured into our soil, air and water. We can set up, or not, needle exchanges for intravenous drgu users, a policy question that routinely gets decided on grounds that have nothing to do with public health considerations. Until government and the body politic have done everything they can to allow people to be healthy, they bear some responsibility for our ill-health.

I close with two smaller points. First, waiting lists. 1.8 million in the UK, Mackey tells us. That statistic means nothing, by itself. First, we need to know what the average wait time is. But then, we also have to compute the average wait time in the US for comparison. We may not have ‘waiting lists’ but anyone knows that if you call a specialist, you might not get an appointment for six months. In Massachusetts, the average wait time for a new patient to see a primary care doctor is 50 days. How do we compute the average wait time in the US? If we simply take all patients who are seen and divide that into the total number of days they have to wait to be seen, we omit one of the most salient facts: that millions of people don’t have to wait at all – because they have no doctors to wait for! Somehow, all the people who have no access to medical care need to be factored in, or the comparison of wait times will tell us nothing. (Obvious, right? If doctors just cut their patient-lists in half, the average wait time should be cut in half. But you’d have all those people with no doctor to go to.) I don’t have any idea how they should be factored in to computing the average wait time in the US, but the point is obvious: better to wait than to die.

Finally, just a quick response to the quote from Margaret Thatcher that Mackey begins his piece with:

The problem with socialism is that eventually you run out of other people’s money.

Maybe so. But it takes a lot longer than it does to run out of your own money!

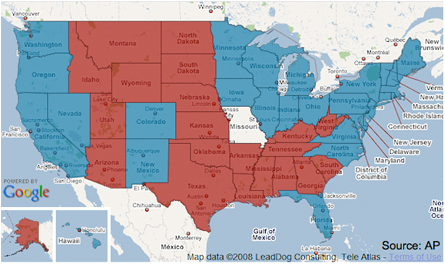

what to make of this, but note that the red states on the map are topologically connected while the blue states are not. That is, you could travel through all the red states without ever having to go through a blue one, but not vice versa. (This will remain true however Missouri and Nebraska 02 go.)

what to make of this, but note that the red states on the map are topologically connected while the blue states are not. That is, you could travel through all the red states without ever having to go through a blue one, but not vice versa. (This will remain true however Missouri and Nebraska 02 go.)